New In

Difference-in-differences (DID) and DDD models

Stata’s new didregress and xtdidregress commands fit DID and DDD models that control for unobserved group and time effects. didregress can be used with repeated cross-sectional data, where we sample different units of observations at different points in time. xtdidregress is for use with panel (longitudinal) data. These commands provide a unified framework to obtain inference that is appropriate for a variety of study designs.

Difference in differences (DID) offers a nonexperimental technique to estimate the average treatment effect on the treated (ATET) by comparing the difference across time in the differences between outcome means in the control and treatment groups. Hence, the name difference in differences. This technique controls for unobservable time and group characteristics that confound the effect of the treatment on the outcome.

Difference in difference in differences (DDD) adds a control group to the DID framework to account for unobservables group- and time-characteristic interactions that might not be captured by DID. It augments DID with another difference for the new control group. Hence, the name difference in difference in differences.

Examples of treatment effects include examining the effects of a drug regimen on blood pressure, a surgical procedure on mobility, a training program on employment, or an ad campaign on sales.

Highlights

- DID and DDD ATET estimators for repeated cross-sections and panel data

- Wild-bootstrap p-values and confidence intervals

- Bias-corrected standard errors using the Bell and McCaffrey degrees-of-freedom adjustment

- ATET estimates and standard errors using the Donald and Lang method

- Mean-outcome and parallel-trends graphical diagnostics

- Granger-type and parallel-trends tests

Let’s see it work

A health provider wants to study the effect of a new hospital admissions procedure on patient satisfaction using monthly data on patients before and after the new procedure was implemented in some of their hospitals. The health provider will use DID regression to analyze the effect of the new admissions procedure on the hospitals that participated in the program. The outcome of interest is patient satisfaction, satis, and the treatment variable is procedure. We can fit this model using didregress.

. didregress (satis) (procedure), group(hospital) time(month)

The first set of parentheses are used to specify the outcome of interest followed by the covariates in the model. In this case, there are no covariates. The second set of parentheses are used to specify the binary variable that indicates the treated observations, procedure. The group() and time() options are used to construct group and time fixed effects that are included in the model. The variable specified in group() defines the level of clustering for the default cluster–robust standard errors. For this example, we cluster at the hospital level. The results from this command are

Number of groups and treatment time Time variable: month Control: procedure = 0 Treatment: procedure = 1

| Control Treatment | ||

| Group | ||

| hospital | 28 18 | |

| Time | ||

| Minimum | 1 4 | |

| Maximum | 1 4 | |

| Robust | ||

| stais | Coefficient std. err. t P>|t| [95% conf. interval] | |

| ATET | ||

| procedure | ||

| (New | ||

| vs | ||

| Old) | .8479879 .0321121 26.41 0.000 .7833108 .912665 | |

The first table gives information about the control and treatment groups and about treatment timing. The first section tells us that 28 hospitals continued to use the old procedure and 18 hospitals switched to the new one. The second section tells us that all hospitals that implemented the new procedure did so in the 4th time period. If some hospitals had adopted the policy later, the minimum and maximum time of the first treatment would differ.

The second table gives the estimated ATET, 0.85 (95% CI [0.78,0.91]). Treatment hospitals had a 0.85-point increase in patient satisfaction relative to if they hadn’t implemented the new procedure.

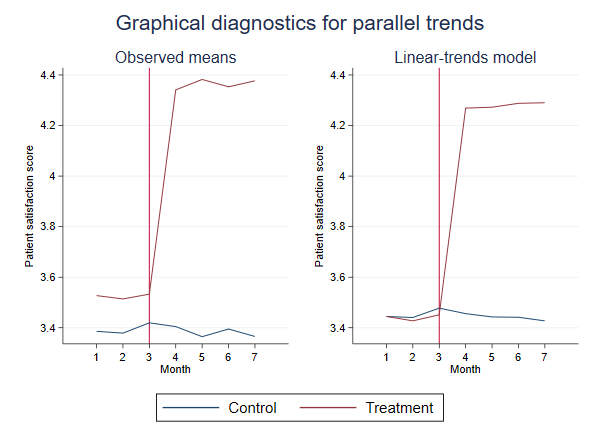

One of the assumptions this model makes is that the trajectories of satis are parallel for the control and treatment groups prior to implementation of the new procedure. A visual check of these trajectories can be obtained by plotting the means of the outcome over time for both groups or by visualizing the results of the linear-trends model. We can perform both of these diagnostic checks using estat trendplots.

. estat trendplots

Prior to the policy implementation, control and treatment hospitals followed a parallel path. We can further evaluate this assumption using a parallel-trends test with estat ptrends.

. estat ptrends Parallel-trends test (pretreatment time period) H0: Linear trends are parallel F(1, 45) = 0.55 Prob > F = 0.4615

We do not have sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis of parallel trends. This test and the graphical analysis support the parallel-trends assumption.

Another test we may want to conduct is to see if, in anticipation of treatment, the control or treatment groups change their behavior. This is evaluated with the Granger causality test using estat granger.

. estat granger Granger causality test H0: No effect in anticipation of treatment F(2, 45) = 0.33 Prob > F = 0.7239

We do not have sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis of no behavior change prior to treatment. Together with our previous diagnostics, these results suggest that we should trust the validity of our ATET estimate.

In this example, we had a sufficient number of hospitals (46) to make reliable inferences about our treatment effect. If we only had data from 15 hospitals, however, we may have considered alternative methods.

To use bias-corrected standard errors with the Bell and McCaffrey (2002) degrees-of-freedom adjustment, we can add the vce(hc2) option.

. didregress (satis) (procedure), group(hospital) time(month) vce(hc2)

To use the aggregation method proposed by Donald and Lang (2007), we can add the aggregate(dlang) option.

. didregress (satis) (procedure), group(hospital) time(month) aggregate(dlang)

We can add the varying option if we wanted to allow some of the coefficients to vary across groups.

. didregress (satis) (procedure), group(hospital) time(month) aggregate(dlang, varying)

We can also use the wild-cluster bootstrap to obtain p-values and confidence intervals. Like all bootstrap-type methods, we need to set a seed to make our results replicable.

. didregress (satis) (procedure), group(hospital) time(month) wildbootstrap(rseed(111)) computing 1000 replications Finding p-value .................................................. 50% ................................................. 100% Confidence interval lower bound ... Confidence interval upper bound ... Number of groups and treatment time Time variable: month Control: procedure = 0 Treatment: procedure = 1

| Control Treatment | ||

| Group | ||

| hospital | 7 8 | |

| Time | ||

| Minimum | 1 4 | |

| Maximum | 1 4 | |

| stais | Coefficient t P>|t| [95% conf. interval] | |

| ATET | ||

| procedure | ||

| (New vs Old) | .860162 19.72 0.000 .7714875 .9587552 | |

The confidence interval and p-value above provide reliable inference for cases where the number of groups is small. These results can be interpreted in the same way as our original model.